Light Peak Explained: New Connection Standard Promises 10 Gbps Or More

Sign up to receive The Snapshot, a free special dispatch from Laptop Mag, in your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

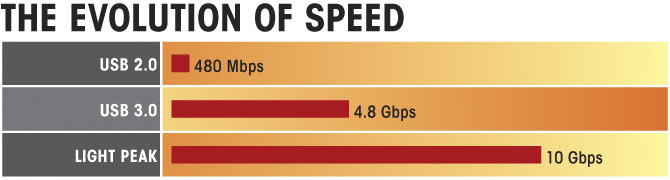

Transfer junkies may be excited for USB 3.0, but Intel’s Light Peak solution promises up to double the speeds of that standard. We’re talking data rates of up to 10 gigabits per second, fast enough to transfer a full 1080p digital copy of No Country for Old Men (about 4GB) in less than 4 seconds (normally a two-hour process). But that’s not all Light Peak can do. To learn more about this exciting technology, we spoke with Victor Krutul, director of the I/O optical team at Intel and a former head Light Peak engineer.

LAPTOP: So how does Light Peak achieve such fast transfer rates?

Victor Krutul: We are reaching the practical limits of how fast you can go with copper interconnects. So when you put electrical signals down a copper wire, you get an electromagnetic wave that goes around it. The problem is, having wires next to each other creates wave interference, which causes electromagnetic interference (EMI), limiting how fast and how far data can travel.

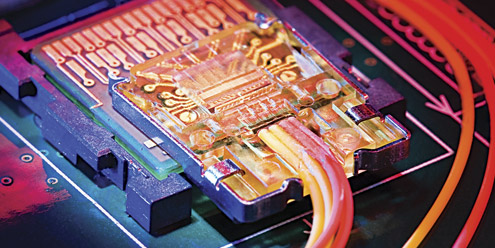

With Light Peak we use lasers, rather than electrical signals. Photons do not interfere with each other the way electrons do, so you don’t have the EMI issue.

LAPTOP: What’s the benefit of using an optical technology?

Krutul: The signaling distances are longer. When making a long-distance phone call, your voice is converted to optical. Likewise, if you’re sending an e-mail to me, our Internet service providers convert it to optical because [optical signals] can go longer distances. Optical undersea cables, for instance, are kilometers long. For Light Peak, we don’t have high-end optical transceivers, but with those you can [send signals] 20 kilometers.

LAPTOP: Do you think Light Peak will replace DisplayPort or HDMI?

Sign up to receive The Snapshot, a free special dispatch from Laptop Mag, in your inbox.

Krutul: It’s not our intention to have DisplayPort or HDMI go away. We support HDMI and DisplayPort on our chipsets and will continue to have those. Higher bandwidth, having one connector with multiple protocols over it, new usage models, cable simplification . . . that’s what [Light Peak] is really about. We complement the other ones. The reality is that HDMI connectors are going to be in our TVs probably until I stop watching TV.

LAPTOP: Is this technology going to work with smart phones?

Krutul: One of our usage models is consumer electronic devices. What’s really happening with smart phones is they are getting more intelligent and want to [consume] content. As long as I have a movie on there, why not allow me to display it on the television? Say I’m on a business trip, I check into my hotel room, and now I want to sit back on the bed. I have a long enough cable—100 meters is more than long enough—so I can sit there in bed, using my phone to control the movie while watching it on TV.

LAPTOP: What are some other usage models?

Krutul: We’re also targeting content creation. As PCs become more powerful, more people are producing content for audio and video. Why go to a studio and pay $50,000 to have them edit it, mix it, dub in sounds, when I can do everything myself? If I’m editing high-def 3D video, I’m already at 10GB of data. And now I’ve got this Light Peak thing where I can talk to [this content] at a high bandwidth and produce near-professional–grade audio and video on a PC, and move it around.

Another thing we’re targeting is solid state drives. They’re much faster [PC storage alternatives], and people are starting to make arrays of them. They’re pretty much in an 8-disk array, wanting 10 Gbps.

LAPTOP: Could you use Light Peak to make notebooks more powerful when docked?

Krutul: Let’s say I want a thin but powerful laptop computer. I want long battery life when I’m carrying it around with me, but when I get it home and dock it, I don’t care about that anymore. I want a screaming workstation. Docks have no intelligence in them whatsoever; they are simply port replicators. Well, why not put high-end graphics in the dock? And as long as I’m doing that, maybe I can put more memory in there, maybe even a higher-end CPU.

LAPTOP: Can Light Peak handle power management? Can it charge devices, too?

Krutul: First of all, on power management: absolutely. If there’s nothing plugged in, we turn the lasers and everything off. We can detect when something is plugged in and wants to do something, or if something is plugged in but inactive; so our power management can save battery life.

Then there’s power delivery to peripherals that don’t have batteries. We can do that, too. In those cases, we have to do it electrically. There’s no efficient way to transfer power optically, at least not right now.

LAPTOP: So I could charge my MP3 player via a Light Peak cord connected to my laptop? What about other devices?

Krutul: It will be able to charge them. We put the electrical wires in the Light Peak cable. It all depends on how much power the device wants. There are such devices—portable printers, for example—that run off your USB port. With USB 3.0, [the power threshold] is 4.5 watts. The threshold of Light Peak is the same.

LAPTOP: Do you have any idea what Light Peak wires will cost, both for the consumer and the manufacturer?

Krutul: Yes, but we’re not talking about pricing right now. So far we’ve announced the technology, and when we actually get ready to start selling, we’ll do a product announcement and each vendor will have its own price list.

LAPTOP: When will Light Peak–enabled products hit the market?

Krutul: We expect both Intel and other vendors to announce component availability later this year, and we’re on track to do that. We have preproduction stuff out now, so internally we’ve built thousands of prototypes. Vendors will start selling them to peripheral makers and computer makers, and we suspect they’ll start shipping products in 2011.

LAPTOP: Over time, Intel claims that Light Peak will be able to obtain 100 Gbps speeds. How?

Krutul: Whenever you design new technology, you have to build in headroom. The rate of 10 Gbps is good enough today for anything you have, but we’d like to see an interconnect that has a 10-plus-year lifetime. Things are always going to get faster.

There is a way to do something called WDM: wavelength division multiplexing. We put multiple colors of light down one fiber, with each laser at a different color or wavelength. Then we can use a prism-like device at both ends to multiplex the lights together, or to split them into separate colors, and convert it all back into electrons. So yes, later generations will scale to more bands of light and an even higher bandwidth.

Kenneth was a Social Media Editor at Laptop Mag. Outside of his limitless knowledge of social media, Kenneth also wrote about a number of tech-related innovations, including laptop reviews (such as the Dell XPS or the Acer Aspire) and even hands-on pieces about printers. Outside of Laptop Mag, Kenneth also worked at our sister site Tom's Guide.