The Netbook Revolution is Over. So What Did You Win?

Congratulations! The netbook revolution is over and you won. Monday, Intel announced the general availability of new systems from most major vendors featuring its dual-core Atom N550 processor. The company also shared that it has shipped over 70 million Atom CPUs since it first launched the low-voltage, low-priced platform back in 2008. Yet with so much success has come massive stagnation—and even declines in sales. The problem isn't that netbooks have failed. On the contrary, they've succeeded so well that they have become irrelevant.

To understand where the revolution went wrong, we must go back to its roots. Like many movements, this one was started by a few idealistic academics. Nicholas Negroponte, formerly of MIT, was the Che of cheap computers, heralding a new era of low-cost, long-lasting laptops that would destroy the digital divide. He started out with a radical agenda, promising sub-$100 laptops to children around the world.

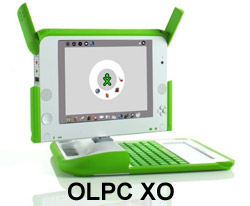

The OLPC laptops would not run a bourgeois operating system like Windows. Instead, they would run Sugar, a special version of Linux, the people's platform. They would even use Marxist technology like mesh networking, which shares an Internet connection "from each computer according to its ability, to each according to its need."

However, as with many radical movements, OLPC's populist ideas didn't put bread—or in this case, little green computers—on the table. Shortages were commonplace and One Laptop Per Child was often more like half a dozen laptops per village. Worse still, trying to surf the Web or compose an e-mail with the XO laptop's cryptic Sugar UI and cramped keyboard was more difficult than trudging through twenty miles of Siberian winter for a tiny ration of spoiled borscht.

As the OLPC-kevites struggled to gain power and influence among the people, their core ideals were co-opted by the man. ASUS's Eee PC 701 gave lip service to Negroponte's radical agenda: small 7-inch size, long battery life, and a Linux OS, but when you peaked below the hood, you saw capitalist components like a Celeron processor and a licensed, proprietary version of Xandros. Still, the original Eee PC had an ideology; it was designed as a secondary device for surfing the Web and sending e-mail only, not as a smaller laptop.

During this early revolutionary period, many interesting ideas were floated. Some companies, like Everex, thought that a gOS-based platform was the future. Others, like Emtec with its Gdium Liberty 1000, wanted to start an anarchist state, so they built a netbook without an operating system or hard drive, and invited the people to bring their own flash drives. In its original Mini-Note, HP even tried a VIA processor that ran hot enough to sterilize a Federline.

But despite these unique experiments, the bourgeois class began to demand creature comforts like 10-inch screens, 5,400 rpm hard drives, and familiar operating systems. Intel obliged by developing its Atom platform, which first appeared in late Spring 2008. Suddenly, everyone from Acer to Viewsonic was building netbooks and Microsoft even lowered its prices for the new category, saying "let them have Windows XP."

Sign up to receive The Snapshot, a free special dispatch from Laptop Mag, in your inbox.

Since that time, the entire notebook world has changed, mostly for the better. Netbooks helped PC manufacturers to focus on low-cost and long battery life. They proved that, for many users, having the fastest processor isn't nearly as important as having a light-weight system that lasts all day on a charge. So netbooks began to morph from the hippie on the corner shouting "down with optical drives" to the CEO in the boardroom, editing spreadsheets on his HP Mini 5102. They grew as large as 12-inches in size, started carrying huge hard drives, and offering HD screens with discrete graphics.

Ultraportable notebooks began to get more affordable too. Where 12- and 13-inch notebooks were once the exclusive province of business executives with over $1,000 to spend, a new generation of ultra-low voltage consumer and small business systems appeared with prices under $600 and battery lives close to those of their netbook counterparts.

So what are your considerable spoils from this revolution? Cheaper, lighter, longer-lasting portable computers. In other words, a huge win.

However, dual-core processors are just the latest in a long line of improvements to the netbook that make it nothing more than a 10 or 11-inch ultraportable laptop, a far cry from its radical beginnings as a secondary web-focused device. How long until vendors give up the ghost, stop calling them netbooks, and begin to market them as 10-inch notebooks? Tiny as they are, many people use them for Microsoft Office, photo editing, or even playing World of Warcraft at a low resolution.

Today's revolutionaries come from the smart phone and tablet worlds. Companies like Apple, Google, HTC, Motorola, and Samsung are the new radicals pushing a web-connected future of secondary devices with many of the leading netbook vendors (ASUS, Acer, HP, MSI, etc) looking to join the insurgency. Let's just hope this generation sticks to its ideals.

Online Editorial Director Avram Piltch oversees the production and infrastructure of LAPTOP's web site. With a reputation as the staff's biggest geek, he has also helped develop a number of LAPTOP's custom tests, including the LAPTOP Battery Test. Catch the Geek's Geek column here every other week or follow Avram on twitter.